enabled the crews to boil the blubber at sea, thus eliminating the need to return home for long periods of time. Life aboard a whale ship was not for men with soft hands. It was a life of cramped living quarters, long periods away from home, bleak meals and hard backbreaking work once a whale was landed. The long days were often spent watching and waiting and preparing the equipment for the hunt. The monotony ended once the spotter called out, "there she blows", which was in reference to a whale spouting a short distance from the ship. Once the spotter sounded the sighting, the crew would spring into action dropping what they were doing and hurry to the best vantage point to confirm the spotting. The Captain would yell back to the spotter, "where away?", in which the spotter would call out the distance and direction. Quickly the ship would set its course to pursue the whale and the hunt was on. A sperm whale had a distinctive spout of being angled forward with a scattered spray. It would spout as many as forty times before sounding (disappearing below the surface) and once it sounded it would disappear for as long as an hour, diving to the bottom of the ocean in search of squid. The intervals between spoutings were fairly equal, thus giving the whale boats an opportunity to set a course for interception. Once the ship was in range, the crews dropped the small whale boats into the water to take up the chase. As they gained on the whale the rowers would put every bit of power into their strokes. Then the header would signal the harpooner, "Stand", and the harpooner would quickly exchange his oars for a harpoon, and get into position. A harpooners job was to get the harpoon deep enough into the whale so that it couldn't break free, if two harpoons could be thrust into the whale, all the better. Once successfully harpooned, the real danger would start. The header would yell "stern all", and the rowers would make it their job to clear the immediate area as quick as possible to avoid the thrashing of the whales' huge tail. Once this was accomplished the crews job was to avoid the unwinding rope as the whale tried to escape the hunters. One crew member would continue to douse the rope with water, to prevent the rope from bursting into flames from the friction, as it unravelled. Most whalemen who were injured, were hurt during this stage of the hunt. An unravelling rope could easily cut through anything that got in its path and with a rough sea and an unpredictable whale, avoiding the rope and a thrashing whale was not an easy task. The rope itself was looped around a loggerhead situated on the stern of the boat and fed up through the bow, this enabled the rope to have drag on it and would, over time, cause the whale to become played out. As the whale dived it would drag the boat at speeds of up to twenty-five miles per hour, in what was called a "Nantucket Sleigh Ride", (also the name of a song by the 1970's band, Mountain, and dedicated to Owen Coffin). Once the whale began to rise again to the surface, the crew would take in the slack rope hand over hand until it once again tightened. If the whale made another break, the rope would once again be let out. This cycle would continue, sometimes for hours until finally the whale would tire and give in. At this point the boat would close in for the final kill. As the boat came along side of the exhausted whale, the header would have the honours of the final blows. Using a lance, he would continue to thrust it into the whale's vital organs. This was known as "tapping the claret bottle" and the whale would usually have one last flurry, colouring the ocean waters red, before rolling over dead. Once the hunt was over the whalers had the task of returning the dead carcass to the ship. If the winds were calm, the boats would have to row the whale, all forty tons or so back to the becalmed ship,

- Page 26 -

a task that could take hours. Once the whale carcass was secured alongside of the ship, a procedure known as flensing would begin. With a hook firmly placed just at the back of the head of the whale, the crew would hoist upward on the rope attached to the hook. Meanwhile, a few of the crew on the whale itself would use flensing spades to cut along the body of the whale toward the tail. The result would be the removal of strips of blubber being stripped off the carcass. These strips would then be lowered below deck to the blubber room. The remaining carcass had the jawbone removed along with the teeth, sperm whales had as many as 46 teeth. The bone and teeth were used for carving or scrimshawing as it was often called. The spermaceti was removed from the head cavity and stored below deck. Often, during the processing of the whale the crew would break into song, happy to know that their families would be looked after once their share of the money was given over to them. One such song entitled "Nantucket Whale Song" sang out;

Oh, the rare old whale, mid storm and gale

In his ocean home will be

A giant in might, where might is right

And king of the boundless sea

After the process of cutting the slabs of blubber into smaller pieces was complete and the weather and seas permitted, the trying out process would start. The tryworks would be lit on the decks and once ready the blubber would be gradually boiled down to extract the whale oil. This process would go on into the night and held a special fascination with the whalemen. The old book, "Etchings of a Whaling Cruise", by J. Ross Browne describes what he witnessed; "I could see the works in full operation during the night. Dense clouds of lurid smoke are curling up toward the tops of the rigging. The oil is hissing in the trypots, with some of the crew sitting on the windlass watching. Their rough weather beaten faces, stare, shining in the red glare of the fires, clothed in greasy duck forming a savage looking bunch as one would ever see. The cooper and one of the mates are raking the fires with long bars of steel and wood. There is a murderous appearance about the blood stained decks with the huge masses of flesh and blubber lying here and there, which inspire in the mind of myself, the novice, a feeling of mingled disgust and awe." Many years later another writer by the name of Herman Melville wrote about the whalers in his famous novel "Moby Dick", a novel based half on fact and half on fiction. Both stories mention the Coffins. Melvilles story has Peter Coffin as the inn keeper at " Spouter's Inn" while the true story that the book was partly based on was about two seperate events involving a Nantucket whale ship named the "Essex" and a white whale named Mocha Dick. The Essex was hunting whales on November 20, 1820, 1200 miles north-east of the Marquesas Islands in the south Pacific. Among her crew was a Nantucket boy named Owen Coffin, son of Hezekiah and Nancy Coffin. Early in the day the crew spotted sperm whales a short distance off and three boats were sent to give chase. Shortly after the hunt began a large whale turned on the Essex and rammed the ship near the bow, sending a shutter through the ship. Badly damaged, the crew tried frantically to fill the hole the whale had made when out of the blue a second crash shook the crippled vessel,- Page 27 -

once again the ship had been rammed by the whale. First mate Owen Chase later commented in his diary, how the whale calculated his attack. "The blows were placed to do us the most injury, the attack could come from only premeditated violence." Within ten minutes the deck of the ship was awash with water and the crew prepared to abandon ship. They grabbed what little they could before the ship heaved to one side and rested almost fully submurged. Many of the crew were staring in disbelief on the fate that lay ahead. They were 1200 miles from land with three small whale boats and next to no food or water. After a day of making makeshift sails the three boats set off for South America. As the days past by, hunger and thirst set in causing squabbling among the crew. On the fourth week a small island was spotted however upon their arrival they found little in the way of food or water, so all but three continued on. Five weeks later a storm separated the boats. By early Febuary with all food and water gone they decided to draw straws to determine who was going to be their next meal. The short straw pointed to Owen Coffin, who by now was past the point of caring. With a show of courage he lay his head on the gunwale and commented, "I like it as well as any other" in reference to his unfortunate pick of the losing draw. Then a shot rang out killing the boy instantly. The boy's sacrifice saw his mates successfully through their ordeal until their rescue by another Nantucket whaler a short time later. In the end, eight of the twenty crew were eventually rescued including Owen Chase who kept a diary of the ordeal. Thirty years later, Chase's son lent the diary to Herman Melville during a whale voyage, and from this diary the foundations of Moby Dick were written.

The period from 1750 to the end of the American Revolution in 1783 was a most eventful time for the whalers. Not only were they venturing further from Nantucket than ever, they also had to avoid French frigates and later British war ships. This period of conflict was a most akward one for the peaceful Quakers. They believed that any form of violence against man, was violence against the god within. They were not permitted to have guns, join militia or pay war tax. They rejected rank and titles and could drink but not get drunk. If ever there was a more perfect ship to attack, the French would have to look hard and wide. Often the Nantucket whalers were attacked and either killed, enslaved or left in a single row boat to die among the elements.By the mid 1750's, Benjamin and Rebecca had nine children, five sons and four daughters. Of their sons, four of them, Elisha, Eliakim, Seth and Bartlett all became whalers. One son Eliakim died at sea in 1784 at the age of twenty-three. Another son, Bartlett married his brother, Eliakim's widow, Judith Macy. Elisha and Seth became sea Captains early in life. Elisha carried his trade to Nova Scotia and P.E.I., while Seth commanded whale ships off the Brazil Banks. In 1800, aboard the ship Minerva, Seth was involved in an incident that reflected the dangers of the whale trade. During a whale chase off the Brazil Banks, Captain Coffin's leg was crushed by a large sperm whale. Coffin quickly realized that his leg had to be removed or he would die. With no one on board with any knowledge of medical skills, Coffin commanded the most reliable mate on board to fetch a flensing spade and return to his quarters. Upon the mates return, Coffin took the spade and was reported to have said, "My leg has got to come off or I will die. I know how it

- Page 28 -

should be done and will instruct you how to do it. If you flinch one bit, I'll send this instrument through you. Now begin". The mate began the procedure, carefully following his Captain's instructions. As the last bandage was properly administered completing the amputation, Coffin fainted followed shortly after by the mate. Seth Coffin later went on to live to the ripe old age of seventy-seven.

In the early 1760's Benjamin and Rebecca's son, Elisha took advantage of the British land grants in Nova Scotia and relocated to Cape Sable Island. Rebecca's brothers, Uriah and Peleg also took advantage of this opportunity. Nantucket was changing rapidly with the success of the whale trade, however, with the trade came an influx of new ships and crews and with these new settlers came problems such as civil disobedience and disease. In 1763 yellow fever hit the Island, taking the lives of many, especially in the Indian population. It is impossible to know if yellow fever was responsible for the death of Benjamin's wife, Rebecca, during this time, but the records show her death occurring on October 12, 1764 at the age of forty three. Benjamin was left with his children ranging in ages of three years to twenty four. It stayed this way for only a short period of time. On April 3, 1766, Benjamin remarried a woman named Hannah Bunker, daughter of Jabez and Hannah Bunker of Nantucket. Benjamin and Hannah resided in the town of Sherburne. As the 1770's approached, all was not well in Colonial America. A movement against Britain was threatening peace in America.

Many mainlanders wanted independence from Britain and were embarking on acts of disobedience. At the heart of the matter was the issue of taxes being levied on the Colonists. This conflict was escalated by an incident involving three Nantucket whale ships. Since 1745, the Nantucket whalers were shipping their whale oil to Britain. On the return voyage they would often carry goods back to America. On one such voyage, three Nantucket whalers, the "Dartmouth", the "Beaver" and the "Eleanor", returned from Britain with a load of tea, destined for Boston. The Beaver was owned by Hezekiah Coffin. Hesekiah was the son of Benjamin's first cousin, Zacheus.The three Nantucket ships arrived in Boston Harbour in early December 1773. On December 16th, they were boarded by angry Revolutionists from Boston, who were protesting against the British government's high taxes without representation. The mob seized the cargo of tea and emptied the tea into the harbour. Today this event is remembered as the "Boston Tea Party". Boston during this period had many Nantucket Coffins living there. Most were descendants of Benjamin's Uncle, Nathaniel Coffin and a Coffin history would not be complete without their mention. Nathaniel was a sea Captain. His son William relocated to Boston and became a wealthy ship owner and merchant. His brother, John, also came to Boston where he opened a distillery and shipping business. William's son, Nathaniel became the Cashier of Customs for the British in Boston, just prior to the American Revolution. Nathaniel was a despised man by many of the Revolutionists and became an enemy to the rebels, as were most of

- Page 29 -

the Coffins of Boston for remaining loyal to the British. As the conflict erupted in 1775, two of Nathaniel's (the cashier) sons, John and Isaac, entered the British Navy. John Coffin's sailing skills put him in command of a British frigate soon after his entry into the service. As the British were scrambling to get troops from Britain to Boston, to quell the rebels, John was ordered by General Howe, the Commander of the British troops in America to help take him and his army to America.

Meanwhile, the British troops in America had their advance inland from Boston halted at Concord, thanks to the warning to the rebels by Paul Revere, that the "British were Coming". From Concord, the British were put on a defensive and had to retreat back toward Boston, being ambushed and slaughtered all the way to a location just north of Boston, known as Bunker Hill. It was here at Bunker Hill that the British troops had to wait for reinforcements from Britain. As they waited, 10,000 Rebels were taking up positions around their encampment. The British fleet, including Coffin's ship landed in Boston on June 15th, and shortly thereafter on June 17th, Coffin landed his regiment at Bunker Hill. It was on the request of his Colonel to "come and watch the fun", that Coffin found himself fighting hand to hand combat with the Rebel forces. After three charges, the British took control of the battle and of Boston and so the long seige began. After the battle, Coffin was rewarded for his bravery and presented the rank of "Ensign on the Field", by General Howe. Shortly afterwards, he was promoted again to a Lieutenant. When the British decided to evacuate Boston on March 17, 1776, Coffin was offered to command 400 men in New York. His men became known as the "Orange Rangers" and consisted of mainly mounted rifle soldiers. In 1777, the Orange Rangers helped to defeat George Washington in the Battle of Long Island. By 1778, Coffin found himself in the south, namely Georgia, where he commanded a calvary unit made up of loyal planters. His bravery in the battles of Savannah and Hobkirks Hill, along with the battle of Cross Creek, won Coffin high praise from his superiors as well as respect from the Rebels.

Major Coffin opened the battle at Eutaw Springs, when he and a few of his men, while out digging up yams came across the advancing Rebel forces of Gen. Green. His fire drew the attention of the British troops and averted a surprise attack by the Rebels. At the end of the fighting in Virginia, Lord Cornwallis awarded Coffin with a sword and a letter informing him of his new rank of Major. As the war was coming to a close and the British found themselves on the defensive, Coffin fought valiantly for Cornwallis, but with the French and American troops surrounding Yorktown, the British army's fate was all but sealed. During these last days before the surrender and with the British troops facing starvation, Coffin and his men staged daring raids behind enemy lines to find food for the British soldiers.

One account tells of a raid on a wealthy planter, whose home was being prepared for his daughter's wedding. Coffin walked up to the door, knocked and waited until the head of the house appeared. Calmly he informed the man of his intentions on taking some of the wedding meal back to his troops and warned the man that any resistance would be met with force. The

- Page 30 -

planter, having heard of Coffin's reputation, did not resist, in fact he invited Coffin in to meet the guests and sit at the head table.

While Coffin's men gathered up the food, Major Coffin sat and spoke with the host, later he danced with the bride before slipping away into the night with his men back into the woods.

During the closing days of the war, the Rebels posted a 10,000 dollar reward for Coffin's capture, but it was never collected. Coffin headed back north through enemy lines and presented himself to the Commander and Chief of the British forces, Sir Guy Carleton. Carleton appointed him Major of the Kings American Regiment. As the war came to an end, the British Government secured Coffin's safety to New Brunswick, where in October of 1783, he landed at a trading post now called Saint Johns. At the young age of 28, he laid down his sword and started his new life in a new land. His new home was located twelve miles north of Saint Johns in a town now called Westfield. Here John Coffin built a beautiful home which he called "Alwington Manor", after the Coffin's ancestral home in Devon England. Coffin was named Magistrate for the county and later became a member for the Provincial Parliament. Coffin's honour saw him involved in no less than four duels during his years in Parliament. He was injured once in the arm but other than that came through unscathed. One such duel was held at sunrise, across the Saint John River, from Fredrickton, in the woods.

In 1812, Coffin raised a regiment for the war with the Americans, but was too far from the battles to contribute. At the end of the war he was promoted to General. Coffin died in 1838 at the age of 82 and was remembered as the oldest General in the British Army. In 1995, I visited the grave of General Coffin at a place called Woodsman Point, high above the St. Johns River in Westfield, New Brunswick. The humble gravestone is shaded by a huge oak tree that was planted as a sappling at the head of the General's grave by his friends and relatives during the burial. Today, the same towering oak now stands as a monument to General Coffin, and the years that have gone by since his death.

In Nantucket the war was a severe blow to the whaling industry as well as the Quaker faith. Many Quakers supported the Rebel cause and even helped them out financially. Many were disowned by the Quakers for this position. One list I came across has a "Benjamin Coffin" listed as being disowned by the Quakers for financial support to the Rebels cause. Was this our Benjamin? We'll probably never know. By 1775, Nantucket had many Benjamin Coffins among their population, and not enough information on who was who. During the Revolution the whale trade had come to a halt. Of the 150 whaling boats in Nantucket, 134 were captured by the British and French with 15 never being heard from again. Some estimates put the losses of Nantucket men as high as 1600, nearly one third of the population. Eight of the men were listed as Coffins. One of Benjamin's sons, Eliakim, survived the war only to die a year later aboard a whaler off the Brazil banks in 1784. As the war ended the whale trade eventually regained its steam and later, in the 1800's, would see itself regain its rightful place as the leader in American

- Page 31 -

whale oil production.

Benjamin Coffin continued to live out his final days in the town of Sherbourne where his will, dated January 4, 1783, was first drawn up. It lists his wife Hannah, his sons Elisha, Benjamin, Seth, Bartlett and Eliakim along with his daughters Rebecca Gardner, Luranna Coffin, Susanna Pinkham and Ruth Coffin. Benjamin died in Nantucket on December 28, 1793 at the age of 75 and is more than likely buried in the old Quaker burying ground where as many as 7,000 Quakers lie in unmarked graves. Most were simply wrapped in cloth from sails and buried.The Children of Benjamin and Rebecca:

Elisha Coffin was born in Nantucket on March 21, 1740. He married Eunice Myrick, daughter of Andrew and Jedida Myrick before moving to Nova Scotia and St. John Island (P.E.I.). Elisha was a fisherman/whaler who also became a member of the first parliament of P.E.I. in 1772. Elisha died October 29, 1785.

Rebekah Coffin was born March 4, 1742 in Nantucket. She married George Gardner, son of Grafton and Abigail Gardner. Rebekah died in October of 1826.

Luranna Coffin was born April 12, 1746. She married Zebdial Coffin, son of Peleg Coffin. Luranna died on December 5, 1821.

Susanna Coffin was born in Nantucket on September 6, 1748. She married Jethro Pinkham, son of Theop and Deborah Pinkham. Susanna died on July 1, 1827.

Seth Coffin was born on June 25, 1753. Seth married Lydia Myrick, daughter of Jonathan and Deborah Myrick. Seth was a Captain of a whale ship named Minerva. He lost his leg during a hunt off the Brazil banks. Seth died on January 16, 1830.

Ruth Coffin was born on May 15, 1755. She married Elijah Coffin, son of David and Abigail Coffin.

Bartlett Coffin was born on June 14, 1756 on Nantucket. He married Sarah Coffin, daughter of Richard and Mary Coffin. His second wife was Judith Starbuck, widow of his brother Eliakim Coffin. Bartlett was a whaler. He died at sea on February 9, 1793.

Eliakim Coffin was born April 29, 1761. He married Judith Starbuck, daughter of William and Mary Starbuck. Eliakim was lost at sea in 1784.

- Page 32 -

RE: COFFIN FAMILY Oct. 14/06

Dear fellow researchers,

It has come to my attention during recent research that a probable error of facts, has put a portion of my previous research for my essay, My Father's Shoes, into question. Recently, I was able to purchase a copy of Barrington Township by Edwin Crowell, a book I have been wanting for some time. As some of you know Crowell stated that Elisha Coffin sen. was bought out by Hezekiah Smith and settled as a farmer in P.E.I.. This statement however small, was important to Coffin researchers, seeing as it provided a link to the path of the first Coffin to come to P.E.I.

Further research showed us that Elisha Coffin landed in Barrington N.S. in 1762 and settled at Centerville Cape Sable Isand. In or about 1772, as Crowell stated, Elisha Coffin left for P.E.I.The problem is that the Elisha Coffin that landed in 1762 in Barrington was not the same one that came to P.E.I., and thus, putting much research into doubt. This became apparent after studying the first census of Barrington dated July 1 1762. The census shows Elisha Coffin with 5 in his family. For some time I thought this was a mistake seeing as our Elisha had only been married for 1 year. Also on the census was a Jonathan Coffin, Simeon Coffin and a John Coffin. After some years of accepting that this was a mistake, I recently had a whim to check my copy of the Coffin Family for any other probable Elisha Coffins that may fit the bill. In a few minutes I had my answer. On page 190 Jonathan Coffin appears with his brothers Simeon and Elisha sons of Nathan and Lydia. While double checking I discovered that Elisha's daughter, Rachel married Edmund Clark the son of a Barrington fisherman. The Elisha Coffin that came to Barrington did have children. Our Elisha, son of Benjamin and Rebecca, therefore, as far as I can tell, had no known connection with the Nantucketers who went to Barrington N.S.. Crowell also stated that Peleg Coffin also came to P.E.I. with Elisha. I have never seen anything to back up this claim. As far as I can tell he went to Liverpool N.S. where he had a fish lot on Coffin Island, an island named after him.

I welcome any comment on my recent research.

Ross Coffin, [email protected]

ELISHA COFFIN SR.

Leaving Nantucket for the North Land

Elisha Coffin was born on March 21, 1740, in Nantucket. He was the son of Benjamin Coffin and Rebecca (Coffin) Coffin. Elisha's mother, Rebecca, was the daughter of Bartlett and Judith Coffin of Nantucket, Massachusetts.

Elisha grew up on the Island of Nantucket during an interesting time, for both the Islanders, and also for the Colonies. The hostilities between Britain, France and Spain were flaring up along the Colonial coastline. This conflict was a danger to the industrious and peaceful people of Nantucket. The Islanders depended on farming, fishing and whaling as a way to make a living. Their religion forbid them to go to war, yet their boats were continually being harassed, confiscated and sunk by their enemies. The French and Spanish ships often chased the smaller, unarmed fishing vessels down and then proceeded to seize the vessels and steal the catches along with capturing the crew. Many times the crews were taken prisoner back to Europe while others were either cast adrift, or murdered in cold blood. The worst of the conflicts for the Islanders was during the 1750's when many Island boats were destroyed by the French. In 1756 they lost six ships that were either heading toward the fishing grounds or home from them. Elisha, during this period, would have likely been a young man learning the skills of a mariner. Boys as young as twelve would often serve on the ships in a limited but necessary capacity. Many of the Captains were as young as twenty.

According to a poem written in 1763, by Thomas Worth, it's revealed in one verse that there were six Captains named Coffin sailing out of Nantucket. The fishing fleets would often set out for six to eight weeks in search of sperm whales. As the years went by the fishing limits grew farther and farther from home, they soon found themselves as far south as the Brazil Banks, off South America and as far north as Greenland in the Davis Inlet. The pursuit of the whales not only brought these hearty Nantucketers fame and fortune, but it was also responsible for some of the migration off the Island. Many left to further explore lands that had been seen during their years with the Nantucket fleets. In the early part of the year, the boats would pursue the whales. At the end of the hunt, after a short stay in port, many ships were refitted and then headed off to the Grand Banks off of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland to continue their trade among the schools of cod.

The Nova Scotia coastline would have been familiar to Elisha Coffin as would the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Many Nantucket mariners were often pursuing the pods of whales and schools of fish in these waters. The Drummond journal of 1771 by William Drummond of P.E.I., states,"May 4, this day saw south winds and heavy rain. Eleven O'clock whaling boats from Nantucket ran aground off Little Hastings(Rustico) Harbour", adding to the evidence that indeed- Page 33 -

many Nantucketers were applying their trade in the St. Lawrence whale grounds. One such whaler was Abraham Coffin, son of Benjamin of Nantucket, who was reluctantly put ashore near Gaspe, Quebec. Some years ago a descendent of Abraham, named Ivan Coffin forwarded the following testimony to me about our Gaspé cousins.

The descendents of the first Coffins to arrive in this country followed different callings, with many of them involved with the sea. Many became ship owners, captains and master mariners. During the later part of the 18th century when whaling was flourishing, many Coffins were involved with that trade. Whaling can be credited with bringing the Coffin family to the shores of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and to the area now known as Gaspé.

The Government of the day offered bounties to all vessels that brought home a designated amount of whale oil. The cargo had to have been obtained by honest means by the crews of the whalers. The bounty was not to be paid for oil that was not produced from the toil of each ship's crew. To protect the government from deception, an affidavit had to be signed by all crew members upon their arrival home. One such vessel, sailing out of Nantucket, in or about the year 1777, carried two crew by the names of Coffin and Davis, who were cousins. The hunt in the Gulf of St. Lawrence whaling grounds, was not a very successful one, and by the time they were ending their hunt, the hold was half empty. Not having enough whale oil to collect the bounty, and with another whaler within sight, the Captain sought a gam with the other Captain. After some negotiations, the two Captains settled on a price and the whale oil was transferred onto the Nantucket whaler. Shortly after, the Captain asked the crew to swear to the false claim that all whale oil was taken only by the ship's crew. Coffin and Davis had a problem swearing to the false oath, having being of the Quaker faith. The Captain became annoyed with his reluctant crew members and threatened them with abandonment on the nearest shore unless they could come to terms with his lie. Fearing God more than the Captain, Coffin and Davis stood their ground. The Captain ordered the ship to head for shore. Having only the clothes on their backs along with an axe, a muzzle loading gun and three days provisions, the Captain bid them farewell at a place known as Cape Gaspé. Once ashore, the two made their way to Peninsula Point where they set up camp for the night under a very large tree. History would later show that Jacques Cartier camped at the same spot on his first voyage to Canada. A few days later the two caught the attention of a passing fisherman who took them across the bay to a tiny Gaspé village. After a short time in the village, Coffin set out in a northerly direction along the shoreline where he came upon large cove. Having the right conditions to start a home, Coffin staked out about a mile of shoreline in which he started his new life. Over time he built a cabin and married a beautiful 16 year old woman named Hannah Ascah. Finding themselves lonely, Coffin soon asked his cousin Davis to come and settle near them. Davis agreed and bought part of Coffin's claim. To the French fishermen, this area was soon named L'Anse aux Cousins or in English, Cove of the Cousins, in recognition of Coffin and Davis, and today the name remains the same.

Abraham Coffin and Hannah had eight children, all but one lived into adulthood.

- Page 34 -

Benjamin, their eldest child, had a large family and settled at L'Anse aux Cousins. Abraham Jr. married Anna Boyle and lived near what is now known as York. Philip Coffin married Margaret McCray and moved across the bay to Farewell Cove.

Back at home, in Nantucket, Elisha Coffin was courting a young lady by the name of Eunice Myrick, the daughter of Andrew and Jedidah Pinkham Myrick of Nantucket. On January 22, 1761 they were married. The Island was finding much prosperity from the money coming in from the whale and fishing trades, however, along with the prosperity came many new problems for the tiny community. Some of the problems came as a result of the many new faces appearing on the Island. Nantucket was unable to supply enough crews from their own people to crew all the boats involved in the trade. As a result whalers from the mainland were recruited. Many ships returned home with crews eager to spend their hard earned pay on wine and women. This was in direct confrontation with the Quakers' lifestyle. The Island meetings tell tale of these concerns. The meetings resolved to hiring watchmen to patrol the streets at night and keep civil peace. In 1761, Elisha Coffin was hired for a one year period to be the Master of the Watch. The new arrivals also brought with them the threat of disease, which in 1763 struck Nantucket's population hard as a ship from Ireland brought with it the dreaded Yellow Fever. This disease hit the Indian population of the Island especially hard, killing many. With the rising problems on Nantucket and the war ending between the French and British, Elisha and Eunice started looking beyond the shores of Nantucket to start a new home.

During 1761, proclamations inviting new settlers to come to Nova Scotia appeared on notices throughout New England. Between 1761 and 1763, about 4,500 settlers arrived from the Colonies to the fourteen newly established townships in Nova Scotia. Among the new arrivals were four Coffin families from Nantucket, they included John Coffin, fisherman and shipbuilder, Peleg Coffin who was a fisherman/farmer. Simeon Coffin and lastly, Elisha Coffin who was a mariner being referred to in the Mog Book as Captain Elisha Coffin.

Research has shown that these families arrived as early as 1761. However the same research shows the family of Elisha Coffin as having four children upon their arrival, which would have been quite an achievement for the newlywed couple. Their children continued to have their birth place recorded as Nantucket right up to their son Kimble who was born there August 8, 1768, and given this evidence, I conclude that Elisha's first property entitlement in Nova Scotia would have been his fish lot while his home remained in Nantucket. It wasn't until the census of 1770 that this family appear as residents for the first time. Many of the New England fishermen found it convenient to come to the Barrington Nova Scotia area in the spring, fish during the summer and return back home in the fall.

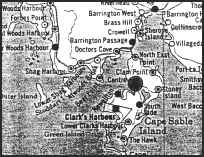

Elisha's property was located on the southern most tip of the territory of Nova Scotia, which was called Cape Island, also known as Cape Sable Island. It is recorded in the Mog Book that he was one of the partners in the Tract of Land Centerville. The record does not address

- Page 35 -

who his partners were. The Mog Book also states, "The Coffin's, after their arrival from Nantucket built and operated fishing vessels". Shortly before 1771, Elisha was bought out by Hezekiah, son of Archelaus Smith, and left with his family and Peleg Coffin for St. John's Island (PEI). There has been confusion about Elisha based on conflicting dates re his arrival on St. Johns Island. Documention to clarify the family history: the Barrington Propietors Book p.30, p.42 1768 describes land allotted to Elisha. In 1769 when town lots were drawn Elisha received Lot#1. There is a record book for 1773 but no records for 1771 or 1772 and the period up to 1784 when minutes were kept again. On page 110 there is a notation re the second division of land (1784) of Elisha Coffin "purchased by Hezekiah Smith". (note that it's in the past tense) The date of 1771, corresponds with the date that Archelaus Smith first came upon Cape Sable Island and where today a museum has been erected giving honour to Smith's name. Also of interest is the fact that the Queens County Deed Book 1: p. 49 shows Peleg Coffin selling his whole share of land on Cape Island including his Islands south of Barrington, on June 21 1771, the year Crowell stated that Elisha and Peleg moved to St. Johns Island. The Coffin Island located near Cape Sable was named after Peleg Coffin. This was once where his fish lot was located. The town of Coffinscroft, formerly known as "the town", south of Barrington, Nova Scotia, was named in recognition of descendants of John Coffin's family and most likely named in honour of Hon. Thomas Coffin, a federal member of parliament in the 1880's. Today one can visit "The Old Meeting House" museum in Barrington, which was erected by the Coffins and others in 1765. The building served as a religious meeting place for all preachers of the gospel as well as a place to hold community meetings and elections. Nearby lies the graveyard where many of the early townspeople are buried.

Perhaps the migration of Elisha from Nova Scotia to St. John Island was the result of recruiting agents being sent to Shelburne, Nova Scotia by the Governor of the Island, Walter Patterson. Patterson wanted to recruit new settlers for his sparsely populated Island (less than 1,000 residents) so that he could form the Island's first Government. About 600 settlers responded throughout the territory, settling on the sandy shores around Hillsborough and Bedeque Bays. Another possibility was that the Coffins from Cape Sable were invited to come to St. John's Island by the Attorney General, Philip Callbeck. Callbeck was a brother-in-law and business associate of Nathaniel Coffin of Boston. Nathaniel Coffin was Elisha's second cousin. The reason behind the invitation might have been in attempt to establish a fishing industry on the Island. Callbeck would have been aware that the Nantucketers were familiar with the waters and skilled in this trade and could offer the industry their experience. It is also probable that Callbeck had met Elisha in previous years had Elisha worked his trade in the waters off Prince Edward Island, Callbeck owned the only outfitters store on the Island and Elisha would have needed provisions from time to time, therefore the two could have become aquainted. In 1772 Elisha arrived upon the Island during the formative years of St. John Island's first government and just a decade after the British had taken the Island from the French.

Although the population of the Island was less than 1,000, the Coffins were well

- Page 36 -

represented. Elisha Coffin's family which now consisted of five children along with Elisha and Eunice, settled along the Hillsborough River at a place called Worthy's Point.

Another Coffin who came to the Island was Elisha's uncle Uriah Coffin. Uriah came to the Island in 1773 and settled at the New London colony where he was a sawmill operator. Perhaps Uriah was the saw mill operator mentioned in a diary written by Thomas Curtis, who visited New London near Christmas 1776, Curtis writes. "The man that had the care of the mill was an American. When I entered his house my heart ached to see his distressed family, a wife and eight or nine small children, the oldest not more than ten years. They informed us they had but a small stock of provisions for the winter. Mr. Mellish who was with me , informed them that they should have plenty of fish sent to them soon. We had a drink of water with them and returned home".During these years Chappells Diary mentions many Nantucket ships visiting the Island, the captain of one of the visiting ships was Uriah's brother, Bartlett. Uriah and Bartlett were the brothers of Elisha's mother Rebecca. Bartlett was the captain of the ship "Elizabeth". It is generally accepted that Elisha and Uriah were the first Quakers to settle on the Island. Shortly thereafter the newly formed Assembly made special provisions to allow Quakers to make an "Affirmation", rather than to swear upon the Bible. Uriah's family settled on lot 47 near East Point, where he died in 1806. Another Coffin on the Island was a lady named Ann Coffin who came from a very prosperous and important family in Boston. Her father was Nathaniel Coffin who was a high ranking customs agent for the Crown. Her brothers were about to find fame as high ranking officers during the American Revolution. They were General John Coffin and Admiral Sir Isaac Coffin. Elisha's relationship to Ann was that of being second cousins, once removed. Ann and her husband, Philip Callbeck, lived just outside of Charlottetown on a farm that is now the present location of the St. Elizabeth Hospital.

If one was to give a brief history of the Island, they would have to go back hundreds of years when the first inhabitants, the Micmac Indians came during the spring time from the mainland's of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. They would travel up the Hillsborough River to the east side of Savage Harbour where they would set-up their summer camps to hunt and fish. Savage Harbour was given its name in recognition of its first inhabitants, the Micmac Indians. Geological evidence brought forth by Abraham Gesner in 1846 shows of a mass grave site of Indian remains being found on Canovay Island on the south shore of the Harbour. Years later the "Examiner" newspaper reported that a Mr. Coffin came across this site and had to rebury some skulls after time and erosion had exposed the graves' contents. Evidence on the eastern shore of the harbour indicates where the Pow Wow's took place as well as the location of their summer camps. The first white explorer to site the Island was Jacques Cartier in the 1530's. He recorded the experience as "Discovering the fairest land that one would ever see". The French named this Island Ile St. Jean and after a considerable amount of time established the first settlement at Port Lajoie in 1719. After some failed attempts due to crop failure, lost supply ships and ships lost to privateers, they did manage to start a few settlements such as Brudenell Point and St. Pierre on the

- Page 37 -

north shore. The on going conflicts between Britain and France in the 1740's and 50's saw the Island change hands a few times before the fall of the great French fortress at Louisburg and the French defeat on the Plains of Abraham in Quebec. Shortly after the French defeat, the British took control of the Island. During the Seven Years War the British proceeded with a plan to expel the french settlers, but were stalled to a certain degree by the lack of British transport ships and the ability of the French settlers to hide in the woods. They dispatched Captain Samuel Holland, who served with General Wolfe at the Plains of Abraham, to survey and map out the Island so that a plan of settlement could be drawn up. The Island was annexed to Nova Scotia and Captain Holland divided the land mass into sixty seven lots of roughly 20,000 acres each, as well as dividing the Island into three counties, Prince County on the west side, Queens County in the middle and King County on the east side. Back in London a lottery was held for those who found themselves in favour with the King. Each lot was drawn individually by mainly rich land barons and officers of the Crown. The conditions set upon their entitlements, such as progressive settlement over a designated period of time, were in large part, ignored over the following years.

The new immigrants to the Island found the struggle through the first few years of settlement to be of the utmost challenge. Some of the lots had farms on them that were abandoned by the French, however they were in decrepit shape due to the years of neglect after the french expulsion. Other lots had no previous settlement at all. The book, "History of Mount Stewart", speaks of one settler's account of "intensely cold winters, where one could easily perish outdoors in a mere 15 minutes if left without shelter". In the summer, "the flies and mosquitoes are of the greatest inconvenience, darkening the air around one". The threat of starvation due to crop failure was an ongoing concern. Field mice and locusts often destroyed their crops. The only guaranteed source of food came from the rich fishing grounds that surrounded the Island along with the berries and small game on the Island.

In 1772, Governor Patterson informed Lord Dartmouth, the Governor of Canada, that the population on the Island had increased enough to warrant a Government of its own, for a 1773 session. With Lord Dartmouth's permission, Patterson went ahead and scheduled an election for July 4, 1773. Patterson decided to limit the Members of this newly formed Assembly to 18 representatives. In his words, "I want to have the members as respectable as possible", and thought that there were only about 18 or so on the Island that would even qualify. The Island's first Parliament was elected on schedule on July 4th and included Elisha Coffin, who was now the age of 33. In attendance with Elisha at the first sitting was Nathaniel Coffin, Ann's brother, who was a lawyer for Ann and her husband, Philip Callbeck. Some feel that the Nathaniel Coffin who attended the first sitting was really Ann's father, Nathaniel Sr., Charlottetown just up the road from the waterfront. Today, a plaque marks this location in downtown Charlottetown. The first order of business dealt with overdue rents for properties, mainly farms. It appears that the settlers were in no hurry to pay landlords that lived thousands's of miles away, especially when there laid little hope of ever being able to purchase their properties. This problem persisted for close to one hundred years and was the main reason why the Island developed so slowly. The first session of

- Page 38 -

Parliament lasted ten days and was summed up by the doorman, Edward Ryan, as a "Damn queer Parliament".

In 1774, Governor Patterson decided that there were enough new settlers to call a second election. Elisha was once again elected and elected again in 1776. Between sessions, Elisha was farming and fishing. His family now consisted of sons, Latham 15, Elisha 13, Kimble 8, Benjamin 4, Rueben 3 and Andrew 2 and their daughters Eunice 16 and Margaret (age unknown). The early farmers on the Island mainly used oxen to pull their ploughs with the harvest being laboriously cut with a reaping hook used on wheat and barley and a scythe used for cutting oats. Threshing was done by means of flail and the grain was taken to markets on a two wheel cart on paths too hazardous for anything more. As shown in their final wills and testaments, farm animals such as cows, pigs, oxen, sheep and horses were most valued possessions. Often their wills would designate which animal would go to a certain son. Other problems for the farmers was the back breaking task of clearing land, for much of the Island was covered in forest, wild tea and ferns. Farmers would quite commonly leave the stumps in their fields rather than remove them. Farms along the shorelines often had to deal with drifting sand and erosion and the soil quality was poor. The fertilizer of the day was mainly manure from the barnyard and in later years mussel mud extracted from river bottoms at low tide. It would take approximately 40 cart loads to fertilize one acre.Peace on the Island was broken on the morning of November 17, 1775. The American Revolution was beginning to spill over the borders into parts of Nova Scotia and Quebec. Early in the morning two American vessels - The Lynch and The Franklin, appeared in Charlottetown Harbour. These two schooners which carried 130 men had been sent by General George Washington to intercept two english brigs carrying weapons and supplies to Quebec. The Captains of these ships ignored orders from George Washington not to engage with anyone but the enemy. The American Captains could not resist the temptation that the unarmed colony presented to them. Not sure if they were in danger, the residents of Charlottetown carried on with their day but kept a watchful eye on the ships anchored in the harbour. The acting Governor Philip Callbeck, became somewhat more nervous when the glint of weapons could be seen from the shore as landing parties embarked into smaller boats. Callbeck immediately sent his wife Ann Coffin, to their farm four miles away along the Hillsborough River. He then proceeded down to the landing area to meet with the unwelcome visitors. Little did Callbeck know that he was about to be involved in a military milestone, for it was this encounter that would mark the first ever American invasion on foreign soil.

His greeting was one of disrespect to say the least. He was struck across the mouth and abruptly ordered off the Island on to one of the waiting ships. The Privateers then proceeded to ransack homes and businesses including Callbeck's office and stores. They stripped his house and stores of all provisions and made their way into his wine cellar. After emptying one cask to the

- Page 39 -

dregs, they transported the rest to the waiting boats. Others had made their way into the quarters of his wife Ann, and proceeded smashing and looting. It was here that they came across her private letters that revealed she was none other than the daughter of the hated and despised Loyalist, Nathaniel Coffin, the collector of taxes in Boston. Enraged and drunk they immediately began a search of the town in the hopes that they could find her to cut her throat. It was only the quick thinking of her husband having sent her to their farm that saved her from a nasty demise. After a while the search was abandoned and they headed back to their boats but not before they grabbed a Surveyor General named Mr. Wright and brought him along to their ship. Once on board, the two schooners prepared to sail and were shortly out of sight of towns people. Two weeks later the ships arrived at Winter Harbour, one hundred miles east of General Washington's headquarters. Somewhat annoyed that his men had disobeyed orders, Washington dismissed the Captains from their command and released the prisoners, but kept the stolen property. Callbeck and Wright returned to Nova Scotia aboard a fishing boat glad to escape with their lives, however, Callbeck's financial losses exceeded 2,000 pounds. It is also noteworthy to mention that the provincial seal of the Island has never been seen after this incident, and to this day, a reward stands for its return.

Another attack in Canada during the Revolution also involved a member of the Coffin family. John Coffin who was an uncle to Ann and brother of Nathaniel, reluctantly found himself involved in the conflict. As it turns out John was a wealthy distiller and businessman in pre-revolution Boston. With the conflict erupting in Boston, John decided to remove his family and business to Quebec City for their safety. Shortly after his arrival, word of an American attack on Quebec forced John to fortify his warehouse located at the base of the cliffs. He armed his building with cannons from a British warship that was wintering in the harbour. In late December 1775, General Richard Montgomery had successfully taken Montreal and was heading for Quebec City. General Benedict Arnold approached Quebec from the Maine coastline, the two were to meet up for an assault on Quebec City. On New Year's Eve, before dawn, the Americans attacked in a blinding snow storm. General Arnold was to advance from the North with General Montgomery's troops advancing along the base of the cliffs from the South. Cautiously advancing past one set of barricades Montgomery raised his sword and yelled "Quebec is ours brave boys", and proceeded forward. The Americans were now becoming visible though the swirling snow and on Coffin's orders the cannons fired grapeshot into the advancing army, instantly killing Montgomery and others and sending the rest into retreat.

John Coffin's actions were later praised by the Governor of Canada, Sir Guy Carleton with the following testimony: "The watchfulness of John Coffin, in keeping the guard at the Pres de Ville under arms, awaiting the expected attack, the coolness with which he allowed the Rebels to approach, the spirits which his example kept up among the men and to the critical instant when he directed Captain Barnsfare's fire against Montgomery and his troops, is to be ascribed the repulse of the rebels from that important post where, with their leader they lost all heart'. There can be no question but that the death of Montgomery and the repulse of this attack, saved Quebec and with

- Page 40 -

Quebec, British North America to the British Crown and that of the brave men who did this deed, John Coffin was one of the foremost.

There are many famous paintings portraying Montgomery's final moments during his attack on Quebec, however there has been little acknowledgement of the fact that John Coffin was instrumental in his defeat.

As a last note about the Revolution in America, it should be remembered that the war caused much fragmentation of the various Coffin families in Colonial America. For example, the before mentioned family of Nathaniel Coffin, the Cashier of Customs in Boston had his brothers remain loyal to the Crown while his sisters were loyal to the Rebel cause. In Nantucket, many Coffins were disowned by the Quakers for helping the rebels with sixty enlisted to fight for the Rebels. Among those listed in the book, "Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War", was a private named Elisha Coffin. Was this our Elisha? I can't imagine it was but I found it interesting that he enlisted on September 16, 1777 for a expedition against Nova Scotia. Most of the Boston Coffins were loyal to the British and as a result lost vast fortunes in holdings, but most escaped to safety, either to Nova Scotia or back to England. Many of the Coffins fled with rewards for their capture being offered by the Rebels. General John Coffin had a $10,000 reward on him, while his brother Nathaniel Jr. (who sat with Elisha on the Island's first Assembly) and William were however given the evidence that Nathaniel jr. was actively working on behalf of Callbeck, and who's name appears on property entitlement plans for lot 28 dated March 23 1773, gives us evidence that Nathaniel jr. was visiting the Island at about the time of the first meeting of the Assembly. Another member of note was Captain George Burns, who in later years helped Elisha secure property. Three days after the election the Assembly met for the first time at The Cross Keys Tavern, which was located in wanted for their provocative vandalism. It appears the Coffin boys couldn't sit by and watch the Rebels organized their rebellion. When the Rebels wanted to meet in Boston, they would hoist a flag on what became known as the "Liberty Tree". The Coffin brothers had a simple solution to end this. With the help of a negro friend, the three set out one night and disposed of the trees with an axe. They would have got away with it had the reward of $1,000 offered by the Rebels for the arrest of the guilty party not loosened the tongue of their black friend. They fled to Nova Scotia in the nick of time, with the smell of tar and feathers lingering in the air back in Boston. Their father Nathaniel went to England in 1776 and spent some years seeking some form of compensation from the Crown for his family's loyalty to the King. Having argued he lost everything in Boston, he expected some form of compensation, but his pleas fell on deaf ears and he decided to return to America where he died at sea of stomach gout one day before his arrival in New York.

During this period, the information on the whereabouts of Elisha is sketchy. It is recorded that he was a member of the Legislative Assembly in 1776 and that his son, Joseph, was born in 1778, but as to where his residence was located is a bit of a mystery. Many records suggest that he did not even come to the Island until the early 1780's and that he was a United Empire

- Page 41 -

1770 Census of Barrington, N.S.

Barrington/Coffin Isl Area

Head Men Boys Women Girls Total Prot. American Sam. Hambleton 1 1 1 3 6 6 6 Eldad Nickerson 1 3 1 5 10 10 10 Sam. Wood 1 3 1 3 8 8 8 Jon. Clark 1 2 1 - 4 4 4 Chapman Swain 1 5 1 3 10 10 10 Benj. Gardner 1 2 1 2 6 6 6 Elijah Swain 1 3 1 - 5 5 5 Peleg Coffin 1 - - 1 2 2 2 Judah Crowell 1 3 1 - 5 5 5 Shubal Folger 1 - 1 1 3 3 3 Elisha Coffin 1 3 1 1 6 6 6 Simeon Gardner 1 3 1 2 7 7 7 John Coffin 1 3 1 3 8 8 8 Zacheus Gardner 1 3 1 1 6 6 6 Jos. Worth 1 1 1 2 5 5 5 Solomon Gardener 1 2 1 3 7 7 7 Benj. Folger 1 2 1 4 8 8 8 Jona. Pinkham 1 2 1 3 7 7 7 Solomon Smith Jr. 1 1 1 - 3 3 3 Edmond Clark 1 - 1 2 4 4 4 Sol. Kenwrick Jr. 1 - 1 - 2 2 2 Samuel Osborn 1 - - - 1 1 1 Tim. Briant 1 - - - 1 1 1 David Crowel 1 - - - 1 1 1 Thos. Smith 1 1 1 1 4 4 4 George Fish 1 2 1 - 4 4 4 Jos. Swain 1 - - - 1 1 1 John Swain 1 - - - 1 1 1 Daniel Vincent 1 - - - 1 1 1 Jon. Smith Jr. 1 - 1 - 2 2 2 Jon. Crowel 1 - 1 - 2 2 2 Jos. Atwood 1 - 1 1 3 3 3 Widow Eliz. West - - 1 - 1 1 1 Wm. Laskey 1 1 1 - 3 3 3 Jos. Godfrey 1 3 1 5 10 10 10 David Smith Jr. 1 1 1 2 5 5 5 Benj. Bass 1 2 1 - 4 4 4 Arch. Crowel 1 - 1 - 2 2 2 Jon. Clerk 1 - 1 1 3 3 3

- Page 41B -

Loyalist. This information is inaccurate and does not stand up to even basic challenges.

On September 5, 1783, Elisha's fellow Legislative Assembly friend, Captain George Burns of Stukely, sold to Elisha Coffin of Nantucket Island, 200 acres of land for the consideration of five shillings and the rental of ten pence per acre per year to be paid half yearly. The property is situated on the west side of Savage Harbour on lot 38, beginning at the first cove above the Island known as Governor DesBrisay's Island, thence to run west 100 rods, thence north to the sea, then along the sea coast to the bay to the cove mentioned. This land sale shows that at least some of the landlords were attempting to keep the terms of their original agreement which stated that they would settle at least one Protestant on every 200 acres within ten years. It also shows that the settlers had to pay dearly for every acre. Today there are still some Coffin descendants owning property at Savage Harbour. One such person, Mrs. Fulton Coffin, formally Miss Marjory Hyndman, whose husband was a descendant of Elisha jr.'s son Benjamin, holds title to some of the original Elisha Coffin homestead, which was where the public docks are now located on the west side of Savage Harbour. Upon our conversation I had with her in 1996, it was learned that the original deed for this property was misplaced and lost only recently by Mrs. Coffin's law firm.Shortly after Elisha settled his family at Savage Harbour, things turned for the worst. On October 29, 1785, Elisha Coffin died of undisclosed circumstances. He was 45 years old at the time of his death. The location of his grave is a mystery, but seeing that there were no established grave yards in the area at the time, it is presumed that he was buried on his property, perhaps on the hill that was located between his house and the sea, or perhaps he was lost at sea and his body was never found. Some speculate he was buried at St. Peter's Harbour. Elisha left behind his wife, Eunice and nine children, ages 7 to 25. Eunice continued on at Savage Harbour for many years, eventually dividing her property among her sons. The Island census of 1798 shows Eunice living with their sons Andrew and Joseph. Elisha Jr. is living beside his mother with his family of nine, which is a mystery of sorts since records show that four of his children weren't born until the early 1800's. Kimble is also living on the property with his family of five.

With the death of Elisha the Coffins of Savage Harbour were slowly losing their Quaker faith. In 1801 a Quaker from New England visited the family and afterwards concluded that most of the Quakers had lost their faith or were on the verge of doing so. They lacked the support that a continuing organization might have provided. Eunice was now a member of St. Pauls church in Charlottetown. The death of Eunice was recorded on January 20, 1814, in the diary of Benjamin Chappell and reads as follows,: "Thursday, died yesterday, old Mrs. Coffin at St. Peter's. Eunice was 76 at the time of her death.

Captain Elisha Coffin was a founding member of the Coffins on Prince Edward Island and was remembered quite eloquently by H. D. McEwen, whose family were long time friends and acquaintances with the Coffins. He wrote, " The Coffins bore an unsullied reputation for honesty, industry and integrity and did their part by honest toil to further the prosperity of the Island."- Page 42 -

Children of Elisha and Eunice Coffin:

Eunice Coffin was born in Nantucket in 1760. She married John Morrow, a Quaker, of East Point P.E.I.. Eunice died in 1805.

Latham Coffin was born on October 2, 1761 and died in Nantucket on February 5, 1845. He married Elizabeth Coleman and they had four children. Latham was also the only family member to return to Nantucket.

Elisha Coffin was born on October 9, 1763 in Nantucket. He married Jane Robbins in 1785, they lived at Savage Harbour. Elisha and Jane had eight children. Elisha was a farmer and a member of the Legislative Assembly in 1810. Later he was a Judge for King's County. He died in 1851.

Kimble Coffin was born on August 8, 1768 and married Elizabeth McEwen in 1794. Kimble was a ship builder and farmer and lived at Savage Harbour and St. Peters. Kimble died in October 1830, their family numbered five sons and four daughters.

Margaret Coffin (date of birth unknown) - married John MacEachern in 1788. They lived on Lot 38.

Benjamin Coffin was born on October 20, 1772. In 1794 he married Catherine Sanderson and they lived at Savage Harbour where Benjamin was a farmer. Benjamin was also a member of the Legislative Assembly. He and his wife had eight children. He died prior to 1850.

Reuben Coffin was born on July 25, 1773 and died young.

Andrew Coffin was born on July 17, 1774. He married Frances Sanderson in 1799. They lived at Savage Harbour where Andrew died on December 9, 1853. They had a family of ten children.

Joseph Coffin was born on June 14, 1778. He married Isabella MacKie in 1801. Joseph farmed at Bay Fortune. His date of death is unknown. They had five children.

- Page 43 -

ELISHA COFFIN

Farmer, Judge and Legislative Assembly Member

Elisha Coffin was born October 9,1763 on the Island of Nantucket, Massachusettes. He was the second child of Elisha Coffin and Eunice Myrick Coffin.

Elisha's family moved off Nantucket shortly after his birth, to Cape Sable, Nova Scotia where Elisha's father was involved with fishing and boat building. Shortly after, their family moved onto St. John's Island (P.E.I.) to a place called Worthy's Point, along the Hillsborough River. Elisha's father must have been a fairly educated man, seeing as he was chosen to be a member of the Island's first Legislative Assembly. In 1783 the family settled in Savage Harbour, on the north shore, in King County, having purchased 200 acres from George Burns. This homestead is considered to be the first permanent home on the Island for our Coffin ancestors. Shortly after purchasing the property, Elisha's father died, leaving behind his widow and nine children. Elisha was 22 at the time of his father's death, his older brother Latham was 24.

In 1785, Elisha married a woman by the name of Jane Robbins, daughter of William and Helen Robbins of Stanhope, P.E.I. The Robbins family held the distinction of being among the first settlers to come over from Scotland aboard the ship "The Falmouth" in April 1770. The birth date of Jane is thought to have been in 1765, in Scotland. Her father William moved from Stanhope to St. Peters in 1787 and was a half-brother of Duncan McEwen. Both of these families would figure into the Coffin family in later years. In 1788, Elisha and his brother Kimble commenced their ship building operation at Savage Harbour by building the small 17 ton schooner, "Rainbow". In later years Kimble went on to become a major shipbuilder, while Elisha's interest in shipbuilding was that of an investor more than a builder, although he was down on record as being a sea Captain during the early 1820s. Sometime after 1792, Elisha's brother, Latham, headed back to Nantucket to live, leaving Elisha behind as the eldest Coffin son on the Island. Latham married Elizabeth Coleman and had many children. He died at the old age of 84.

During the 1790's, Elisha and Jane were busy raising their children Kimble, Eunice and William. The family, during the 1790's was living on their farm at Savage Harbour, which consisted of 92 acres of his father's original farm. It was during this period of time that the Coffin's of Savage Harbour would receive a very distinguished visitor. Admiral Sir Isaac Coffin was a man who held his Coffin kin, close to his heart, so it was no surprise that when chance had it, he appeared on the shores of Savage Harbour. Elisha's father, Captain Elisha Coffin was the Admiral's second cousin, once removed. Isaac Coffin was born in Boston in 1759. Like most of the Coffin's of that era he developed his sea legs at a very young age. He entered the Royal Navy in 1773 at the age of 14 under the watchful eye of Lt. W. M. Hunter. It was not long after this time that Hunter was quoted as saying, "Of all the young men I ever had care of, none answered my expectations equal to Isaac Coffin, never did I know a man to acquire so much nautical

- Page 44 -

A Frontier Trading Post, c.a. 1780

- Page 44a -

knowledge in so short a time". Coffin's rapid rise up the ladder in the British Navy leaves little doubt of his brilliance. At the age of 19, Lt. Coffin was commanding the Cutter "Placentia". At the age of 20 he was serving under Admiral Pasley aboard the frigate "Sybil". He was the signal Lt. in the action off Cape Henry, at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, in March 1781, during the Revolution. Later that year, he was made a Commander. After seeing action in the Caribbean aboard the "Borfleur" he returned to England where he was called upon to take the newly appointed Governor of Canada, Lord Dorchester (Sir Guy Carleton) and his family, to Quebec.

It was during this period that Isaac Coffin, aboard the frigate "Thisbe", first sighted the Magdalen Islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Half jokingly he asked his friend, Lord Dorchester, to grant him the Islands for his loyal service to the Crown. Dorchester later took it upon himself to set the wheels in motion and raise the issue with King George III. On May 8 1798 The Magdalen Islands were granted to Captain Isaac Coffin. They remained in the Coffin's control for 105 years until 1903 and made Isaac and his heirs very rich men. Although Isaac never lived on the Islands, he made many efforts to advance the Islands forward by introducing healthy livestock and financial support. After Canada was ceded to Great Britain in 1763, the British made little effort to supply official currency for their North American holdings. In 1815, Sir Isaac Coffin became possibly the first one to rectify this by issueing an unofficial copper penny for the Magdalen Islands. The coin had the image of a seal on it with the words,"Magdelan Island Token", on one side and "Success to the Fisheries", on the other. However, the residents, mainly french fishermen, disliked Coffin and showed him little respect. It has been said that Coffin, once tried to expel his tenants on the Island but the British government frowned on the idea. After his death, the control of the Islands went to his nephews, the sons of his brother John and sister Ann. The Islands were later sold to Quebec by a third generation of Isaac's nephews for $100,000.00. It was also during this time that Coffin brought gifts of horses and cattle to Elisha's family at Savage Harbour. History tells of Isaac requesting some of the Coffins of Savage Harbour to relocate onto his newly acquired Islands, but there were no takers. In 1804 Isaac Coffin became a Baronet while serving as a rear Admiral in Nova Scotia. He married Elizabeth Browne in 1811, but later separated due to their intolerance of each other's ways. Back in England in 1818 he served as a member of Parliament for the Borough of Ilchester, and was highly regarded in the House for his naval expertise. It was his love for his homeland back in America that cost him what would have been the crowning jewel to his career. William IV had his friend Sir Isaac Coffin, in line to become Earl of Magdalen and intended to make him the Governor of Canada, however, the British Parliament didn't take kindly to the idea of his appointment due to Coffin's strong American ties. The man himself stood over six feet tall, he was robust and energetic, until an accident at sea injured him severely. Having witnessed a man being swept overboard by a wave, Coffin rescued him by going overboard after him. He saved the man's life, but injured his back in doing so, this injury continued to follow him for the rest of his days. Isaac enjoyed good conversation and had a dry wit. One story tells of a time when he returned to England after one of his numerous voyages across the ocean (40 voyages in his lifetime). Upon his arrival he was

- Page 45 -

informed that a man who was being held in confinement, a prisoner, claimed to be his relative. With his curiosity leading him, he went to the prison to further investigate. To his surprise he was brought to a black man. Both surprised and amused, the coloured man told him that he was an American and therefore must be related, since Coffin was also an American. While listening intently, Coffin finally interjected saying, "Stop, my man, stop! Now let me ask you a question", he said, with a pause, "How old may you be?", "Well", said the black man, "I should guess about 35". "Oh then!", Coffin said, turning to leave, "There must be a mistake, you can't be one of my Coffin's, none turned black before the age of forty". Another story reveals his love and hate relationship with his wife. After a short time of living together they both decided that what their marriage needed was a lot of distance between them. His wife's late night sermons gave Sir Isaac nightmares and the Admirals frolicking about the British taverns caused his wife to write late night sermons. A few years after their mutual agreement to live apart, Mrs. Coffin caught wind that Sir Isaac was about to set sail for Boston. Not being at all behind the fashions of the day, she requested her estranged husband to purchase her a Boston rocking chair while in Boston. Sir Isaac grudgingly agreed and upon his arrival in Boston he located a splendid chair, the best money could buy, but before shipping it back to England, he took a saw and cut a few inches off the back of the rockers, to ensure that every time his dear wife rocked, the chair would tip over backwards, and she would end up on her pompous little fanny.

Admiral Sir Isaac Coffin died July 23, 1839 at the age of 80 and left a good portion of his fortune back in America spread out among his numerous kin. The Coffin school in Nantucket, was just one of Coffin's donations to his friends and family. In later years, Elisha's son, Benjamin Coffin, was asked to describe the old Admiral. His quick reply was "Big feet, long legs and a big nose, just like all the other Coffins".

The late 1790's in P.E.I., saw the first Presbyterian Church in the area being built about one mile south east of Savage Harbour, in what is now West St. Peter's Cemetery. It served a wide area including the Coffins of Savage Harbour. They would travel by boat across the bay in summer and by sled over the bay ice in winter. Upon landing on the south shore, they would remove their shoes for the dusty walk along the trail to the church, so as not to get their best shoes dirty. This church existed for close to ninety years, until being replaced by a new one at Bristol. Elisha's grave lays within feet of where the old church once stood, and is probably one of the few remnants of the church's past history. I suspect it was Elisha's wife, Jane who first introduced Elisha and family to the religion of Scotland, Presbyterianism. It was also from this congregation that one of the Island's most famous Minister's developed. Elisha's grandson, Fulton J. Coffin, son of Elisha's son Benjamin, was born and raised in Savage Harbour. He was educated at Prince of Wales College before heading off to Princeton and Oxford Universities. Reverend Coffin became well acquainted with the leading scholars of the day, not only in North American, but also in Europe and Asia. He eventually settled in Trinidad where he became the principal of the Presbyterian Theological College, a post he held for twenty-five years. He was known as an expert in the Old Testament, and was thoroughly trusted by the East Indian population of the

- Page 46 -

Island. Rev. Coffin was also a noted Hindu scholar, and lectured in their language as well as english. He died in 1936 and was buried in the Peoples Cemetery, in Mount Stewart, P.E.I., where all but one of the gravestones face the rising sun, Rev. Fulton Coffin's faces south, towards his friends in Trinidad.

During the 1790's, Elisha appears on various documents and census reports. A list of subscribers to a copy of a memorial relative to the streets and commons of Charlottetown, presented to Lt. Gov. Fanning dated January 1, 1792, bares Elisha's signature, along with his brothers Latham and Kimble. The Island census for 1798 shows three Coffin families living on Lot 38, which included Savage Harbour. The census shows Kimble Coffin's family of five, two males and three females, Widow Coffin (Eunice) along with her sons Andrew and Joseph, and Elisha's family with nine, five males and four females. Elisha's family in 1798 only consisted of seven, Elisha, Jane, Kimble, Eunice, William, Margaret and Harriet. The leftover persons are two males who are under sixteen and create a mystery as to their identity. The census also shows Uriah Coffin, Elisha's great uncle, living on Lot 47 in East Point with his family of eight.

In 1801, Elisha and Jane had a son named Benjamin. In later years he would become known as "neighbour Ben". In 1803, their son James was born, and two years later in 1805 their daughter Rebecca was born. On February 16, 1805 a congratulatory letter was sent to Lt. Gov. Fanning, upon his retirement from public duty. It was signed, among others, by Elisha Coffin. It was during this time that Elisha was becoming involved in politics. He ran in the 1806 election, and won a seat as a member for Kings County in the Legislative Assembly, alongside his brother Benjamin.

Some of the debates in the house during this session dealt with Loyalist land claims and compensation for broken promises. The Parliament also dealt with regulation of liquor sales. This topic was of interest to Elisha, and possibly even brought to the House by him, seeing as how he had an invested interest. According to the book, "History of Mount Stewart", Elisha was running a tavern in the Mount Stewart area, and so was his younger brother Andrew. It would appear that anyone and everyone who wanted to, was selling rum from their homes. This no doubt would have been taking business away from their established taverns. Another issue that crossed the floor, dealt with, what to do with people who intentionally maimed or killed cattle, and was stated, as a growing problem. Perhaps this issue stemmed from an incident when some privateers sailed up St. Peter's Bay, shot some cattle, turned around, and left. It was also stated that even though Britain was preparing for a possible war, (war of 1812), the government had put aside sixteen hundred pounds, for the erection of government buildings and gaols (jails).

In 1807, the Coffin's daughter Phebe was born. Shortly after or possibly during Phebe's birth, Elisha's wife, Jane died. It is not documented until Phebe's baptism, April 5, 1809, the mother (Jane) is listed as deceased. In 1810, a survey map drawn-up on September 15th, shows Elisha owning 160 acres of farm land at Savage Harbour. This property was part of his father's

- Page 47 -

original purchase. To the north his younger brother Andrew is situated on the coastline with 83 acres and south lies the homestead of his brother Benjamin. Although their mother was still alive, I believe she was now living with her son, Kimble, possibly at St. Peters, where her death was recorded in 1814. Elisha was sworn in as a Justice of the Peace for Kings County in 1812. He was also farming during this period of time, and shows up on the MacDonald ledger (and old merchant's account book), in 1814 as the purchaser of nails, iron and rum. He paid with oats and hay. Elisha continued to live on the north-east shore of Savage Harbour. In 1996, I visited Savage Harbour to view this landscape. As we came down the dusty road toward the harbour, my first observations were the mailboxes along the road on top of fence posts, that read "Coffin", thus telling me that indeed, I was on the right road. The green meadows were bordered by spruce trees. As the red rust coloured road, rounded a bend, I could see the harbour at the bottom of a gently sloping hill. At the base of the hill, I could see small grey fishing shacks by the dock. This is where early maps show Elisha's home being situated. The location is perfectly sheltered from the sea, which lies just north, over a small hill. The mouth of the harbour, has nearly closed off completely from the sea. Only a small channel remains, in which the fishing boats enter and leave. The beach front is wide, flat and rocky and probably very different than it was over one hundred years before. Gone are the forests of evergreen trees and tiny fishing shacks that once dotted the beach, changed by the wind, sea and time. Savage Harbour still remains a beautiful, thought provoking area, bathed in Coffin history.